Arthur Monroe

Overview

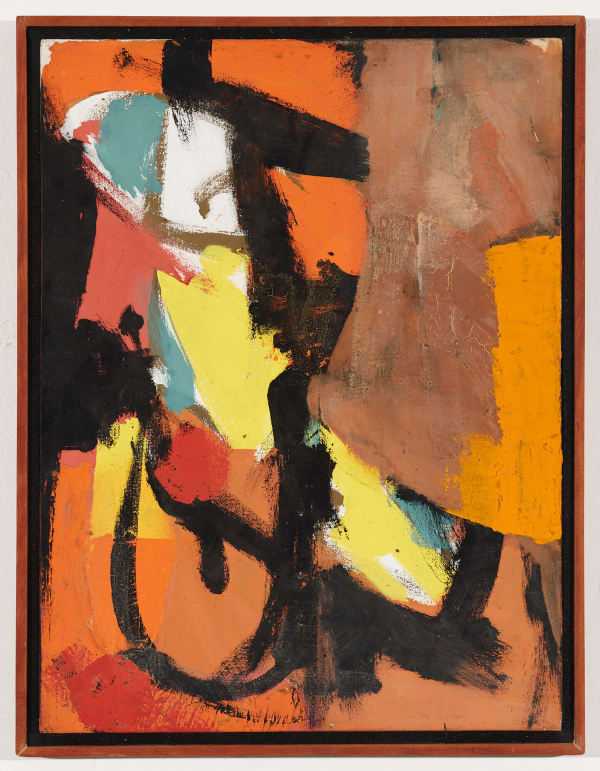

Arthur Monroe (b. 1935, Harlem, NY d. 2019, Oakland, CA) was a respected artist, educator, community activist, Abstract Expressionist painter, and known for his involvement in the Beat Movement of the 1950s. Committed to his abstract expressionist roots, his approach to self-expression and his search for new visual truths can be seen through his labor-intensive process— at one point spending three years on a single painting. Unlike other painters, Monroe worked like a scientist: going through a myriad of questions before arriving at a hypothesis. He approached his materials as a challenge; the more he worked with them, the deeper his appreciation for them and what they might do.

Monroe attended The Boy’s School in in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn and the Brooklyn Museum Art School, in addition to being trained at the Art Students League, where he was mentored by German American painter Hans Hofmann. As an adult, he frequented the infamous Cedar Street Bar and made close friendships with key poets, musicians, and artists of the time Monroe developed a circle including Charlie “Bird” Parker; LeRoi Jones, Max Roach; and Thelonious Monk. Some other associates included acclaimed Abstract Expressionists Norman Lewis, Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, and Jay DeFeo. Monroe’s East Village studio was also across the hall from Willem de Kooning's. After his travels, he served in the Korean War and later moved to California in the 1950s. In the Bay Area, he became immersed in the arts scene and was involved with the Beat Generation of writers, musicians, poets, and painters in San Francisco’s North Beach district. Monroe became a key figure in the movement and San Francisco Renaissance movements, befriending luminaries such as Jack Kerouac, Bob Kaufman and Lawrence ferlinghetti, who became a life-long friend after mounting one of Monroe's first shows of paintings at the seminal City Lights bookstore in 1962. Feeling a need to explore non-European sources of art, he later traveled to Mexico in search of immersion in other cultures that offered different spiritual, philosophical, and aesthetic perspectives. He lived for a period in Ajijic Village in Jalisco, where he was immersed in both the local indigenous culture and a community of expatriate artists, writers and musicians. In 1975, while living in North Beach, Monroe saw an advertisement for a studio space in Oakland and soon moved to the Oakland Cannery on San Leandro Street. He transformed the industrial warehouse into the first legal live-work space for creatives. He made the Cannery his home for the next 43 years, pioneering and advocating for the creation and protection of similar live-work arts spaces.

Monroe was a professor of African American Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, and at San Jose State College. He also worked as a registrar for the Oakland Museum for 35 years. Monroe was the Chair of the Far West Region North Committee for FESTAC 77’, and co-produced FESTAC 75, known as the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. He was also an organizer for the First Statewide Conference of Black Artists held in 1978.

Works

Press

Art Fairs

-

FOG Design + Art 2025

23 - 26 Jan 2025Jenkins Johnson is pleased to participate in FOG Design+Art 2025. Join us in Booth 107 for the Preview Gala on Wednesday January 22 . The...Read more -

Art Basel Miami Beach 2024

6 - 8 Dec 2024Jenkins Johnson Gallery is pleased to participate in the 2024 edition of Art Basel Miami Beach . This year is our largest and most ambitious...Read more